From Stop-Motion to CG

We know that animation is made up of deliberately composed frames, but how do those frames end up on the screen? There are currently three basic techniques used for “capturing” animation, with a few outliers and overlaps.

The first technique is frame-by-frame animation. In frame-by-frame animation, an animator creates each frame individually. This is the oldest technique and, potentially, the most time-consuming. Hand-drawn or cel-based animation is a done frame-by-frame, as is stop-motion. Since each frame is being created, frame-rate is a major consideration for frame-by-frame work. Animation being done at 24 frames-per-second requires twice as many frames to be created as animation done at 12 frames-per-second.

By its very nature, frame-by-frame animation is the most exacting and precise technique used. Every aspect of frame-by-frame animation is controlled by the animator. Hand-drawn animation (such as “classic” Disney films) and stop-motion are the most obvious examples of frame-by-frame animation. In frame-by-frame animation, the animator has to have a good sense of timing, physics, and movement – and how those factors translate into individual static frames. In a way, frame-by-frame animators have to operate in two different states of time simultaneously. The work of animation is done between the frames.

https://youtu.be/EgvfVusJS2k

The second technique is keyframe animation, which evolved from the frame-by-frame technique. In keyframe animation, an animator defines the “key” moments in a sequence and software fills in the blanks. If, for example, we were animating a spaceship moving from one side of the frame to another over two seconds, frame-by-frame animation would require us to create up to 48 individual frames (depending on the frame rate being used). Keyframe animation might only require us to create two frames – the start point and the end point – and animation software would fill in the rest.

That sounds like a huge time savings – and it can be! – but keyframe animation can also be incredibly involved. Keyframing works well for setting start points and end points, but often animation involved multiple things moving at different rhythms simultaneously. For example, a person walking is moving almost every part of their body – upper and lower arms, upper and lower legs, hands, head, hips, torso – and all of those parts need to be keyframed separately in a way that appears seamless and natural.

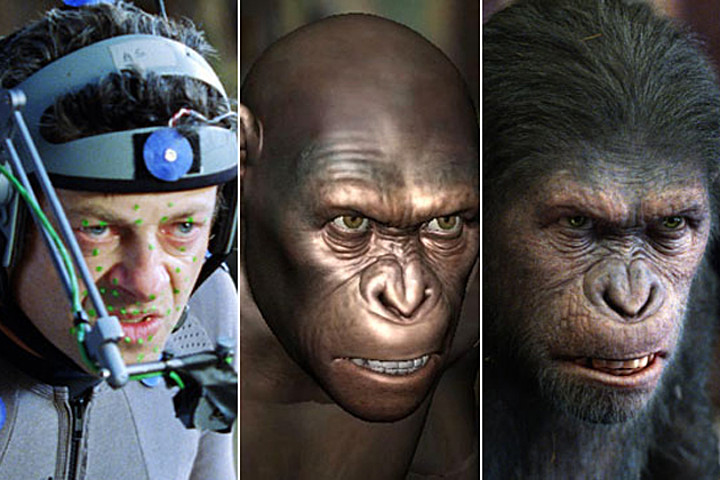

The third technique is motion capture. This is the newest animation technique and the one that requires the most specialized knowledge and software. In motion capture, an actor wears a special suit (or make up, for facial motion capture) covered with reflective dots that can be tracked by software. As the actor moves, a camera interprets the movement of the dots and applies them to the movement of an animated character. Sometimes this is done after the fact and sometimes it is done instantaneously.

Because motion capture is created using “real world” movement, it can be used to create animation that is realistic and subtle. Motion capture is often used in the special effects industry, where believability is of the utmost importance. It is also commonly used to create animation for video games.

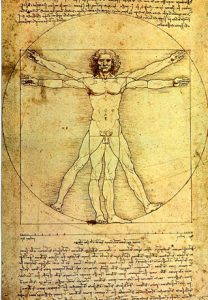

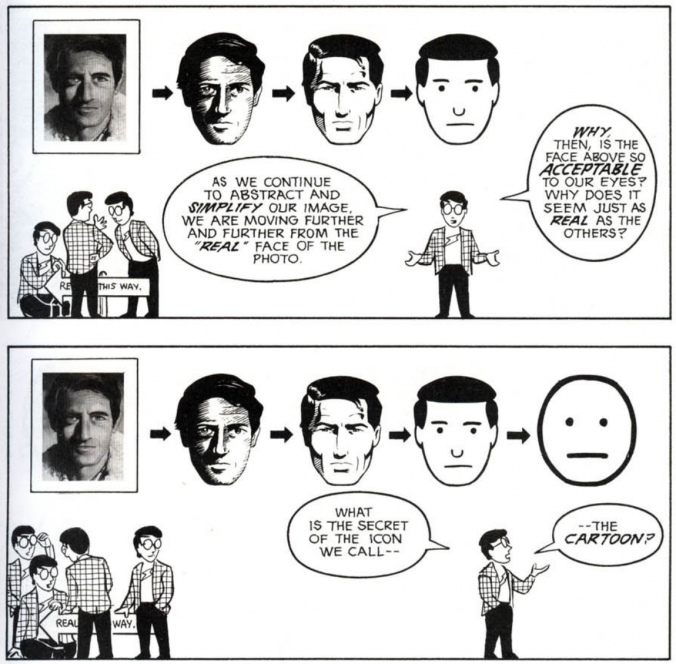

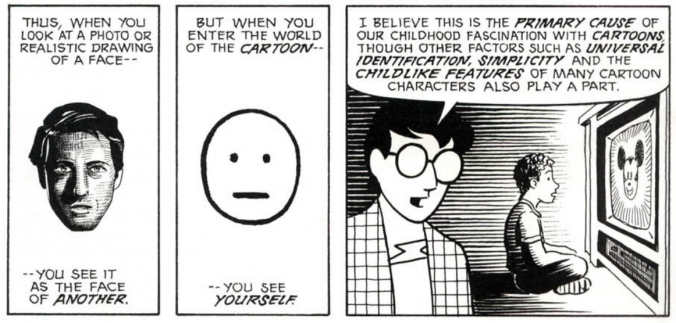

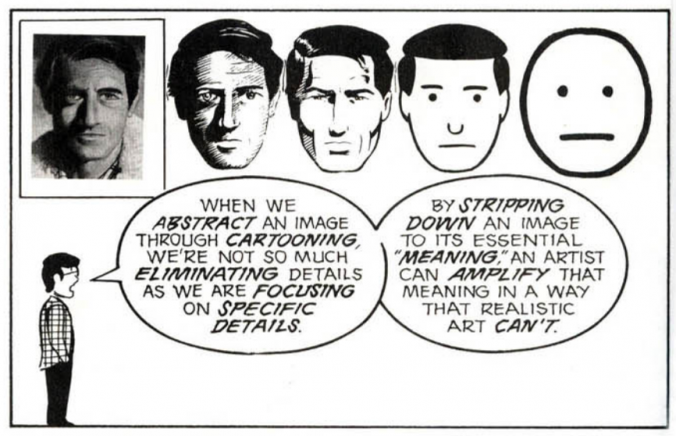

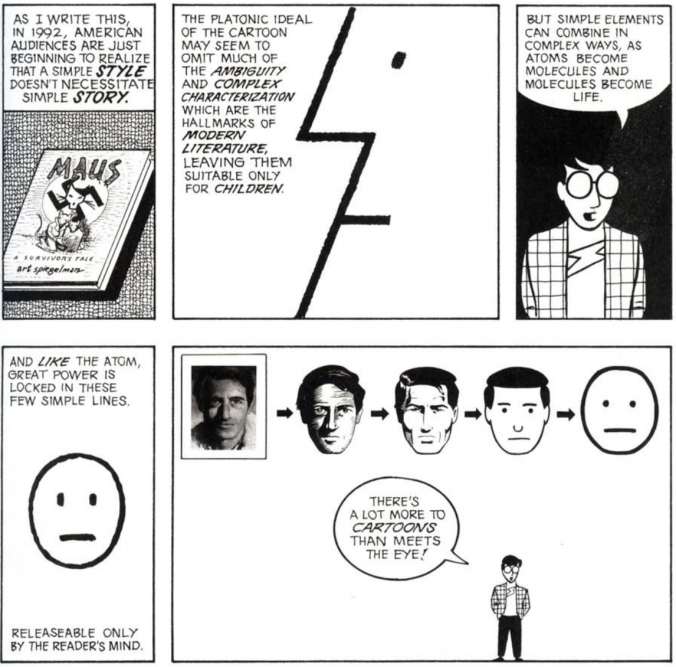

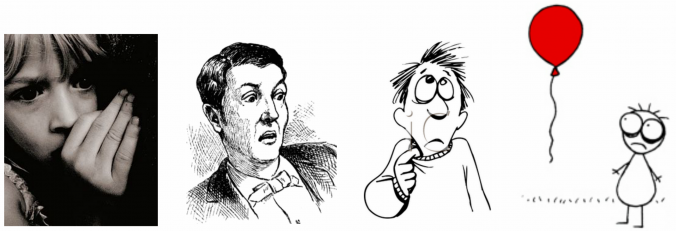

The biggest benefits of motion capture are speed, realism, and the ability to improvise. A motion capture actor can collaborate in the animation process – keyframe and frame-by-frame techniques rely solely on the animator. The downside of motion capture is that it can introduce too much realism – or, perhaps, the wrong kind of realism – into the animation process. When we watch something that we know is animated, we accept (and even anticipate) a certain level of exaggeration and a certain level of simplification. This relates back to our discussion of “iconic” imagery. Animation that looks nearly real, but seems just slightly “off” can be incredibly distracting. The industry term for this phenomenon is the “uncanny valley.” Animated films like The Polar Express have been criticized for looking too real to be cartoons and too cartoony to be real. The uncanny valley refers to this disconnect with regard to both visual representation and movement.

While these three categories of animation might initially seem distinct and clearly defined, they often overlap with each other. For example, keyframe or frame-by-frame techniques are often used to tweak and refine motion captured animation. Frame-by-frame animation is often started by a “key” animator, who only draws the keyframes. This work is then passed off to “in-between” animators, who fill in the gaps, essentially acting like human animation software. There are also some techniques that defy easy categorization. Marionette or puppet-based films are not truly animated, but they fit the definition of iconic cartoon representation. Rotoscoping, a technique wherein live-action photography is covered with cartoon art, falls somewhere motion capture and the other techniques. There are also still-image-based films (also called “diaporamas”) that are composed of frames in sequence, but do not give the illusion of movement.

The 12 Principles

As mentioned earlier, one reason that the so-called “uncanny valley” is a problem is that we don’t expect animated things to move in a completely realistic way. Of course, the effectiveness of animation is determined by more than realism. The best guide for how movement should be animated probably comes from two former Disney animators named Ollie Johnston and Frank Thomas in their book Illusion of Life. Johnston and Thomas defined twelve “basic principles” that animators should master. They are as follows:

- Squash and Stretch – The idea that the shape of objects and characters is flexible and determined by their movement. The classic example is of a rubber ball elongating as it falls and squishing down as it hits the ground.

- Anticipation – This is a small action that precedes a larger one, such as when you duck down slightly before jumping.

- Staging – This deals with the way a scene is arranged. Ideally, it should direct the viewer’s attention in a clear way.

- Straight Ahead Action andPose To Pose – Essentially, this is the difference between frame-by-frame (straight ahead) and keyframe (pose to pose) animation.

- Follow Through and Overlapping Action – These two techniques help animation seem more natural. In follow through, moving objects tend to keep moving past their destination because of inertia; for example, your arm keeps swinging after you throw a baseball. Overlapping action is the movement of multiple objects or body parts simultaneously, but at different rhythms or speeds.

- Slow In and Slow Out: generally, objects in motion don’t move at a steady rate. Instead, they accelerate or decelerate depending on a number of factors. Slow in and slow out can tell the viewer a lot about an object’s weight, mass, and speed.

- Arc – Things very rarely move in perfectly straight lines – most action follows an arc trajectory. A thrown ball will move in a rounder or flatter arc depending on its speed. Walking is composed of small arcs from step to step.

- Secondary Action – This is a smaller action added by the animator to emphasize a bigger one. Things like facial expressions and hand gestures are often used as secondary actions.

- Timing – In its simplest terms, timing describes how long animated actions take to occur. Johnston and Thomas are specifically referring to the number of frames an action takes and how manipulating that number can change the meaning of that action.

- Exaggeration – The amount of exaggeration in animation is largely determined by the level of realism in the work. Often, exaggeration is used for comedic effect in animation.

- Solid Drawing – In two-dimensional animation, the animator should consider how the character or object would exist in three-dimensional space. This helps give things mass, weight, and balance. Without solid drawing, things tend to appear flat and floaty.

- Appeal – This relates to character design. Animated characters should be pleasing to look at. This doesn’t necessarily mean that they must by physically attractive, but they should be interesting to the eye. Exaggerating proportions and playing with shape is a good way to do this.

For an excellent and concise explanation of each of the twelve basic principles, check out Alan Becker’s series on YouTube.

Keep in mind that Johnston and Thomas’s principles are just that – principles, not hard-and-fast rules. Squash and stretch or exaggeration can be used to varying degrees to make a piece more realistic or more cartoony. The principle of solid drawing could be ignored to make a piece deliberately surreal. Whether you follow the principles closely or purposely break them, the most important thing is that you understand and consider them as you move forward with your own animated projects.

Project 2: Frame By Frame

For your first animation assignment, I’d like you to create something without the use of a computer. It can be done using stop-motion puppetry, paper cut-outs, collage, drawing on paper, drawing with chalk or a white board, or another “hands-on” technique. Create at least five seconds of animation at a minimum average of 12 frames-per-second (in other words, you must create at least 60 frames). Plan it out in advance and, as you work, keep the basic principles of animation in mind.

The easiest way to capture your animation is probably using your phone. There are a number of free apps for creating animation; I’d suggest Stop Motion Studio, which is available for both Android and iPhone. Stop Motion Studio allows you to take photos within the app and choose the frame rate at which they play back. If you’d rather hand draw your animation, that’s fine too. There is a cool app called Animation Desk that allows you to draw frames within the program. Both apps are fairly intuitive and there are lots of resources online if you get stuck.

If you decide to do stop motion, one challenge is going to be keeping your phone steady as you work. You may want to consider securing your phone to a stable surface using rubber bands, tape, or clay. Even just leaning your phone up against something can help a lot. You will probably have to do some problem-solving and improvising to make things work – have fun and get creative! There are also a limited number of phone mounts and small tripods in the equipment collection. The library Equipment Services may have options as well.

Animating frame-by-frame like this is time-consuming and difficult to master. Don’t get discouraged! Seeing animation that you’ve created with your own hands come to life is incredibly rewarding. The goal here is to get a better understanding of things like motion, speed, and timing.

When your animation is finished, export the video and email it to me at dan014@bucknell.edu. If your file happens to be too big to email, drop it in your Google Drive storage and send me a link. Happy animating!