The Illusion of Movement

To study animation, I believe that it’s important to understand two central aspects of the form: one is technical and the other is aesthetic. The technical aspect of animation deals with the mechanics of its creation – how animation, in it various forms, is made. The aesthetic aspect of animation examines the unique qualities of animation as a medium, as opposed to other forms (such as live-action cinema, photography, and literature). Put simply, these two aspects comprise how animation works and what animation can do as a medium.

To get started, let’s get some very basic definitions out of the way. At its most basic, animation is the illusion of movement created by viewing a series of images in rapid succession. The base element of animation – the frame – is not meant to be viewed individually, but as part of a larger whole. This means that a flip book is animated, since the images therein are viewed sequentially, but a comic book is not, since the panels that make it up are considered individually.

The root of the word “animate” translates roughly to “instill with life” – processes within the brain breathe movement into static images when they are viewed one-after-another at high speed. This illusion is commonly referred to as “persistence of vision,” which is technically incorrect, but has a nice poetic ring to it. By definition, all film and video – live action or otherwise – is animated, since all film is made up of individual frames that have the illusion of movement when played together. To avoid confusion and adhere to the common usage of the word, we’ll limit our definition of the term to works that use representative art instead of photography.

However, it’s vital to appreciate how intertwined “cartoon” animation and live action cinema really are. While animation is often dismissed as a childish offshoot of “real” film, on a technical level, live-action cinema is actually a subcategory of animation.

The Evolution of Animation

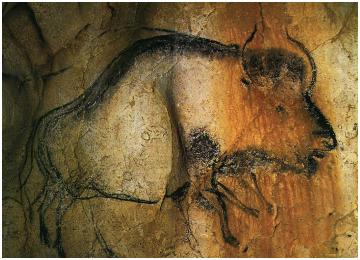

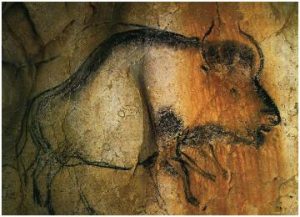

Animation is old. It can be traced back to the very inception of cinema and beyond – potentially, much further beyond. With an open mind and a bit of imagination, you can connect animation to the dawn of art and civilization itself. In the beautifully preserved cave paintings in Chauvet Cave (located in southern France) you can find horses and bison drawn with extra limbs and lions that seem to rush forward. Some scholars have theorized that prehistoric people would have seen the illusion of movement in these images, watching them through the flickering light of a cave fire. They are estimated to date between 32,000 and 30,000 B.C.E.

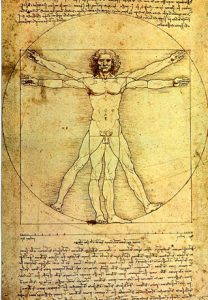

There are several other examples of pre-cinema animation from through human history. An Iranian bowl dating from around 3,000 B.C.E. shows a goat leaping into a tree in multiple “frames.” Some Egyptian hieroglyphics show sequential movement and the multiple limbs in DaVinci’s Vitruvian Man imply movement in the same way that the paintings in Chauvet Cave do.

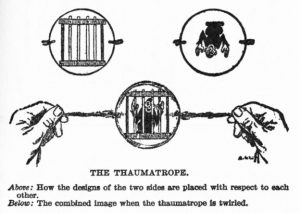

In the roughly 300 years before the birth of cinema, the precursors of animation took the form of toys and curiousities, such as the magic lantern, thaumatrope, zoetrope, flip book, and praxinoscope. Eadweard Muybridge’s famous photographic studies of galloping horses were another milestone – more explicitly than ever before, they divided fluid movement into static frames.

In 1892, (a year before Edison invented the kinetoscope and two years before the Lumiere brothers invented the cinematograph) Charles-Émile Reynaud debuted the Théâtre Optique in Paris. Reynaud showed a series of short films, each comprised of 300 to 700 painted frames of animation. These frames were strung together into what was essentially a filmstrip and projected using a magic lantern.

The development of motion picture cameras brought animation to a state that more closely resembles its current form. The Humorous Phases of Funny Faces (1906) by J. Stuart Blackton is often cited as one of the earliest examples, although Emile Cohl’s Fantasmagorie (1908) captures animated movement in a much more sophisticated manner. The brilliant illustrator Winsor McCay debuted his Gertie the Dinosaur cartoons in 1914. McCay even incorporated himself into the action, interacting with the animated Gertie in a well-timed theatrical performance.

It’s believed that the first feature-length animated film was the 1917 Argentinian political satire El Apóstol, which was tragically lost when fire destroyed the only known print. The oldest surviving animated feature is the 1922 film The Adventures of Prince Achmed by Lotte Reiniger. Reiniger painstakingly created the film using intricate paper cutouts. The resulting film was then hand-tinted, creating a striking aesthetic.

The evolution of animation throughout the twentieth century includes too many milestones to list here. A few highlights include:

- The rise of Disney in the late 1920s, with Steamboat Willie

- The “golden age” of American animation (including the work of Warner Brothers, MGM, Fleischer Studios, and Disney) from the 1930s through the 1950

- The explosion of animated television programs beginning in the 1960s

- Pioneers like Ralph Bakshi in the 1970s and 1980s, who pushed animation into more adult territory

- Pixar’s groundbreaking work in the 1980s and 1990s in the world of computer animation, most significantly with the release of Toy Story in 1995.

For a lovely visual representation of the history on animation, check out this site: https://history-of-animation.webflow.io

Of course this is only a brief – and admittedly U.S.-centric – overview. Animation has branched out into styles and techniques too varied to cover and you can find fascinating examples from every corner of the globe. Notably, in Japan, animation has a position of cultural importance that is difficult to overstate – but that goes far beyond the scope of what we can cover here. There are simply too many rabbit holes to follow.

With that caveat in place, here are a few video essays exploring the work of a few very different animators: Chuck Jones, Brad Bird, John Kricfalusi, and Satoshi Kon.

The Language of Symbols

What do you see below?

: )

A face? A human face tied to a specific emotion? Why would something so simple call to mind something as complex as a human being experiencing the concept of happiness? This is the sort of question that pertains to all visual art, of course, but something about the illusion of life in animation makes it seem especially relevant.

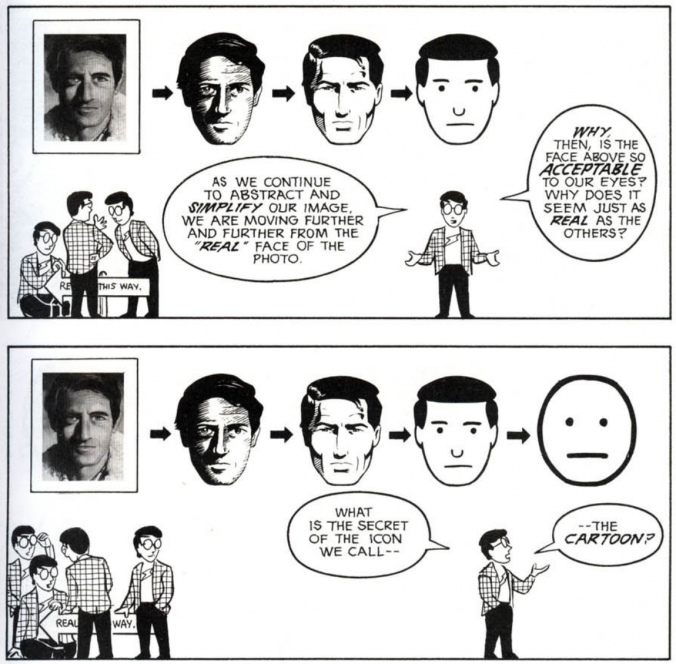

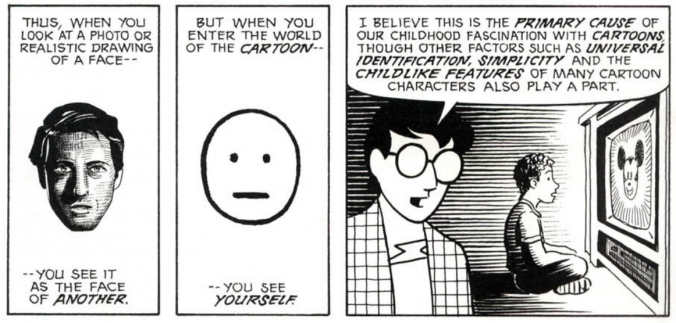

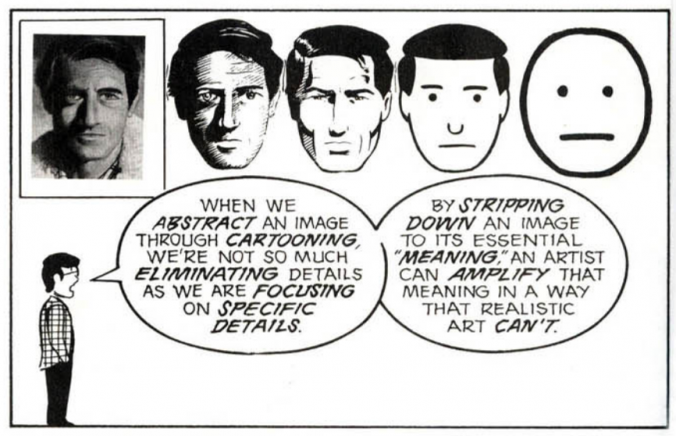

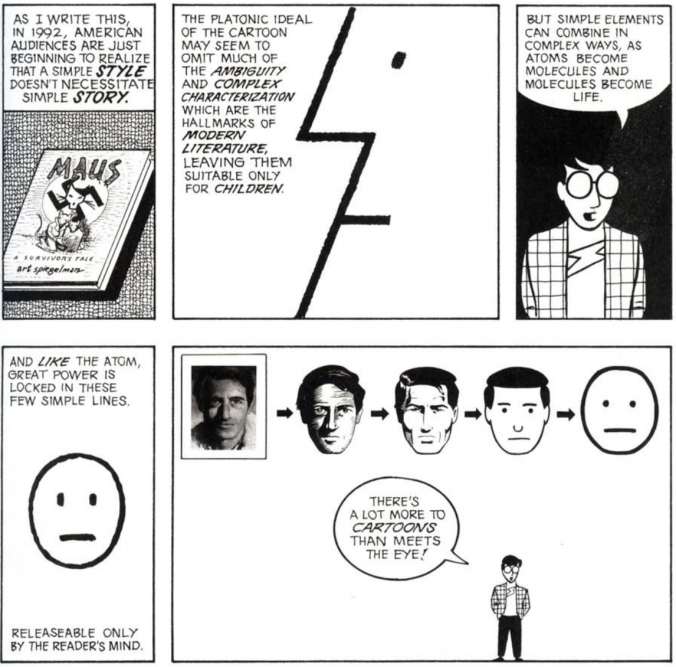

I’m going to borrow pretty heavily from Scott McCloud and his excellent Understanding Comicsfor this discussion. McCloud is obviously focused on comics, but a lot of what he writes about is applicable to animation as well. In his chapter “The Vocabulary of Comics,” McCloud spends a lot of time talking about what he calls icons and how the level of visual realism they carry imbues them with different qualities.

McCloud argues that cartoon icons – simplified visual representations of real-world things – contain a unique power. For one, the generalization present in cartoon representation allows the viewer to project themselves into the character. McCloud ties this to the fascination that children have with animated characters.

Another power of cartoon representation lies in its ability to magnify certain qualities of the character or thing being shown. Because cartoons use fewer elements (details, shading, realistic proportions, etc.), the elements that are present become incredibly potent.

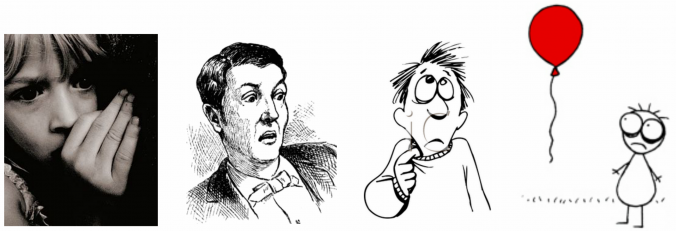

In the following images, the idea of nervousness or fear is shown with decreasing realism. While the photograph is potent, it’s also complex and specific. The stick figure (which is from Don Hertzfeldt’s Billy’s Balloon) conveys a similar emotion with far greater economy – and, potentially, more power. Just as an exercise, consider this: the last time a movie made you really emotional, was it live-action or animated?

To close, here are a few clips from short films by Don Hertzfeldt, one of my favorite animators. His work appears simple at a glance, but the animation is meticulously drawn and his work manages to be simultaneously absurd, tragic, and hilarious. I think the Hertzfeldt’s work exemplifies the kind of iconic power that animation possesses.

Project 1: Watch This

I think that it’s really important to watch lots of animation if you’re going to create animation. For your first assignment, I’d like you to watch an animated short film. There are lots of channels dedicated to animation on YouTube and Vimeo; you could also try a site like Cartoon Hangover, Cartoon Brew, or Short of the Week. There are endless options, just find something interesting. It can be any length, just keep it under 20 minutes. It must be available to watch (legally) online.

Once you’ve found your short film, write a few sentences about why you think it’s interesting. How does the animator use imagery and sound? Are any clever editing techniques being used? Are the characters iconic or more realistic? Just write up a brief analysis of the film and email it to me (dan014@bucknell.edu) with a link to the film itself. Send them to me by next Thursday morning at the latest, so that I can review the films and post them online before class.